After the success of the abortion speak-out, radical feminists used this tactic to publicise an issue that had never before been made visible: rape. In an interview with Nanette Rainone, one of four (unnamed) members of New York Radical Feminists answer her question about the inspiration for their January 24 1971 Rape Speak-Out saying:

“part of it was realizing what had occurred when Redstockings took over the abortion hearings and turned it into an abortion speak out. This was the first-time abortion came out into the open…One of the things we're trying to do is bring rape out into the open. For too many years we have felt guilty about it – we have been made to feel guilty...and we're tired. Rape is not our fault; rape is something that is done to us and we're protesting.”1

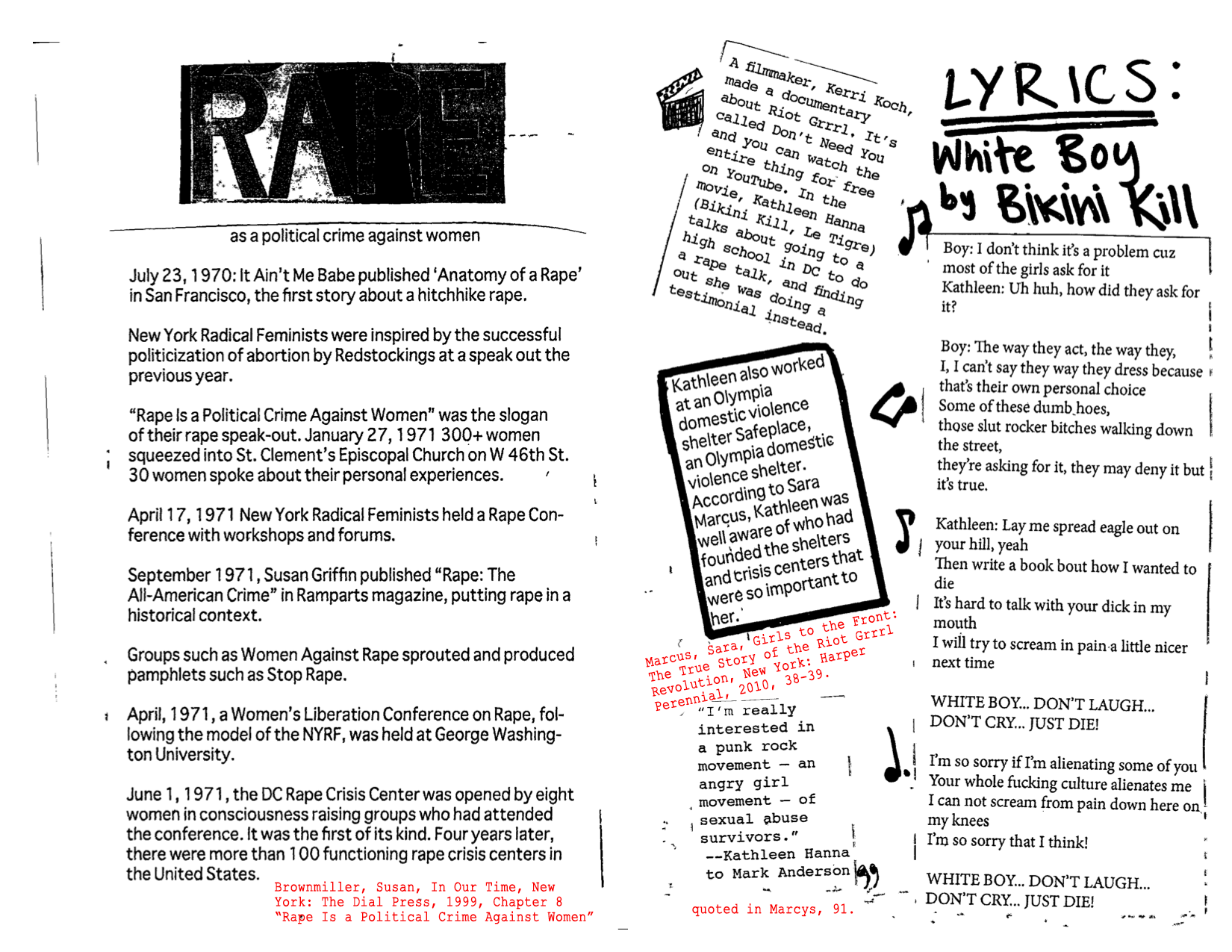

NYRF thought that, if enough women publicly shared their experiences, rape would stop being considered a personal experience and the world would realise it was political. When Riot Grrrl zines contain testimonials by women who have survived sexual assault, they aim at the same thing. The de-stigmatization of the rape victim relies first on rape’s visibility as a political and gendered crime. However, this notion was not easy for everyone to come around to.

For the Old Left, rape was only political when it was “the false accusation of white women against black men that lay behind some accounts of southern lynching.”2 Susan Brownmiller, who had been involved in the civil rights movement of the ‘60s, told me over the phone how she had held this view, and why it had changed. “The minute rape was raised it was raised all over the country – [It Ain’t Me] Babe, which was based in San Francisco, published the first story about a hitchhike rape. Diane Crothers from the Stanton-Anthony brigade brought a copy of It Ain’t Me Babe to meeting one week. She came late, she dropped it on the table and said: ‘This is our new issue.’”3 Susan went on to say that it was the fact that two women in her group had a rape experience, and the realization that not everyone was as wary as her, that changed her mind. This anecdote in itself demonstrates the power of the testimonial, especially when it is personal. For Susan, this was in a consciousness-raising meeting where those telling their stories were her friends. However, with its familiar girly cursive and DIY aesthetic that invites you to join in, Riot Grrrl has a similar power.

The legacy of the Women’s Liberation Movement was not confined to the testimonials of their meetings and writings. In an iconic image of Kathleen Hanna taken in 1992, she is topless with the word “SLUT” scrawled across her stomach in black marker.4 The reclamation of gendered slurs also finds its roots in the actions of the late sixties and seventies. Alix spoke to me about the modern phenomenon of SlutWalk, saying “we embodied the term. We embodied all those terms; bitch, slut.”5 The “Take Back the Night” walks carried on into the days of Riot Grrrl, and continue to this day.6 This legacy of women taking up space in which they are normally unwelcome can be found in almost everything the Riot Grrrl did. They were girls taking over the mosh-pits, girls taking over punk-rock tours, and girls taking control of their own cultural consumption and political power. Rape was an issue that Kathleen Hanna rallied her supporters around, and she knew that the rape crisis centers at which she had worked only existed because of the work done by the second wave.7

1. https://archive.org/details/pacifica_radio_archives-BB3958.04

2. Brownmiller, Susan, In Our Time, New York: The Dial House, 1999, 198.

3. Brownmiller, Susan, Personal Interview, Zoe Guttenplan, 05/12/16.

4. http://dazedimg.dazedgroup.netdna-cdn.com/723/azure/dazed-prod/1110/7/1117587.jpg

5. Shulman, Alix Kates, Personal Interview, Zoe Guttenplan, 30/11/16.

6. Baumgardner, Jennifer, F 'em!: Goo Goo, Gaga, and Some Thoughts on Balls, Berkeley, CA: Seal Press, 2011, 234.

7. Ibid, 49.