Activism today, especially activism surrounding topics such as sexual assault, has learned a lot from the Women’s Liberation Movement. The way that it is centered around personal narrative, the testimonial format, the embracing of topics traditionally seen as taboo in a public setting; “we started that,” Alix Shulman said.1 The first speak-out, held by Redstockings on March 21, 1969 was on abortion.2 The speak-out followed their heavily publicised protest at a New York state hearing on proposed liberalising amendments to the New York abortion law. The ‘expert’ testimony came from fourteen men and one nun; Redstockings demanded that all abortion law be repealed as “the only real experts on abortion are women!”3

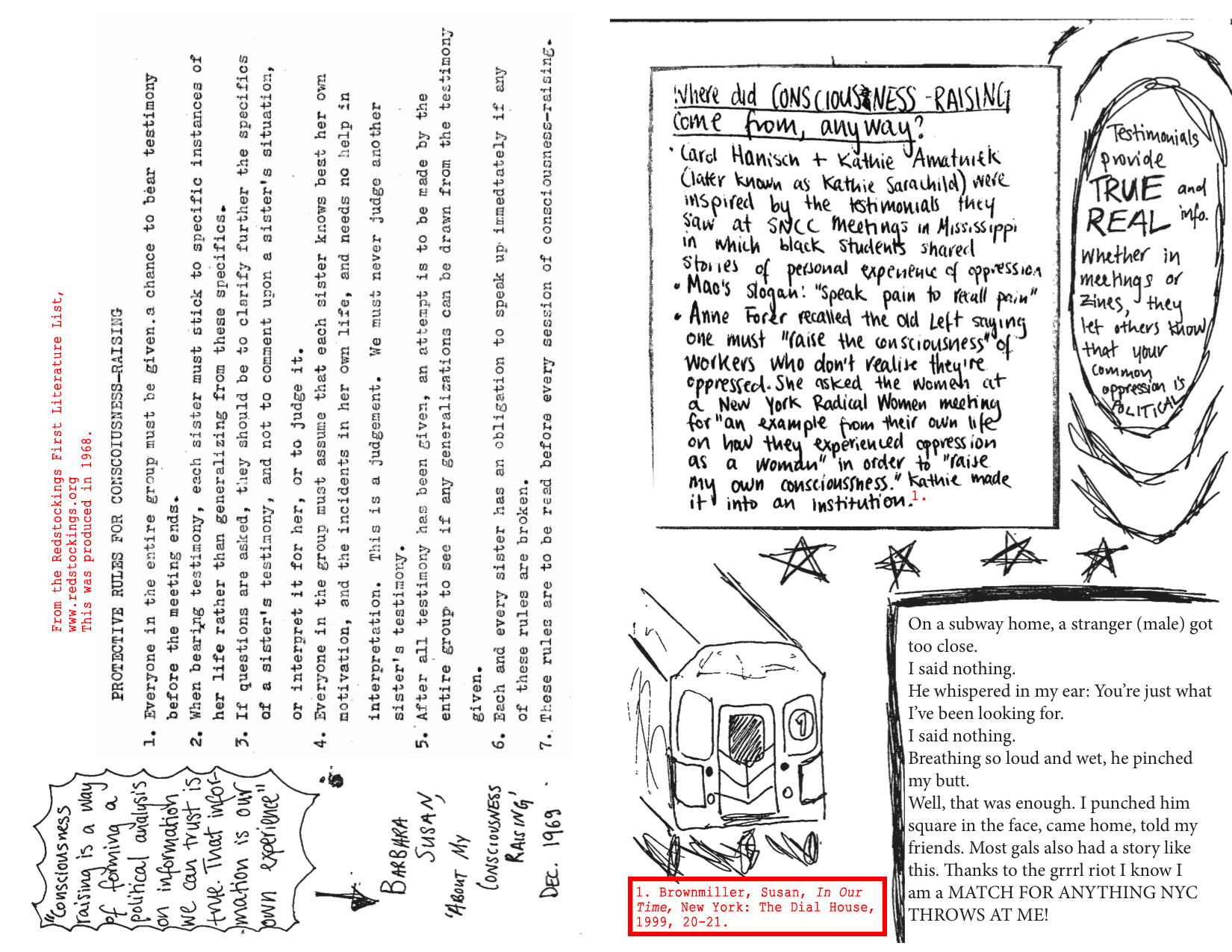

Although I don’t wish to follow the trail of zine culture all the way back to the first ‘underground’ publication, when it comes to speak-outs it is important to give credit where credit is due. The personal testimony was a big part of Riot Grrrl as well as the Women’s Liberation Movement. Beyond women telling their stories at Riot Grrrl meetings, or on stage, the zines themselves acted as a sort of stage for the stories these girls had been afraid to tell for a multitude of reasons. Grrrl zines are characterized in part by making public that which society tells women to keep private, as well as their aesthetic and technology of production. Just as consciousness raising was inspired by the testimonials at SNCC meetings, Irene Peslikis locates the inspiration for the “tell it like it is” abortion speak-out in “the black movement, the civil rights movement.” She argues, “you have to defend your own rights. Nobody’s going to do it for you. You have to tell the truth about what’s going on.”4

The consciousness-raising meetings on which the abortion speak-out and later speak-outs were modelled happened weekly. “It was a face to face movement,” Alix said. “We told each other everything at meetings.”5 The parallel to the Riot Grrrl meetings in which girls shared their personal stories in a girl-centric space is not coincidental.6 However, Alix and the other members of the consciousness-raising groups were “very adamant to distinguish [them]selves from group therapy. This wasn’t therapy – [they] were figuring out how to change the world.”7 The purpose of these meetings instead “was to find out the truth about women though our experiences because all the books were written by men. To raise your consciousness was to become aware of the condition of women that had not been mentioned in our lifetime.”8

The books in Alix’s apartment are split between two separate sets of bookshelves: one for women and one for men. At any moment in our conversation, she would remember a book that I must read, and walk over to the women’s shelf. Assuring me that there was some kind of categorization system, she would find the book in question, pull it out, and bring it to the sofa, leafing through the index as she went. “All the books used to be on the men’s shelf,” she said, “except for a small collection of books by women. Eventually that section grew and I had to move it. Now it’s much, much bigger!” This last statement was accompanied by a proud smile. Many of the writers on the female side are good friends of Alix’s, or at least people she campaigned with. There is a camaraderie that is evident in the sideways smiles and warm tones she uses to talk about Susan Brownmiller, Shulamith Firestone, Ellen Willis, and many more. Perhaps, that is the most striking similarity between Riot Grrrl and the Women’s Liberation Movement: the community of women that each built.

For both movements, members reflect on the community that they built with emotion, awe, and wonder. “Women…seeing their interests as one…was the most wonderful thing that ever, ever happened” for Anne Forer.9 Although this sentiment is given with the benefit of hindsight and perhaps the rosy tint of nostalgia, Riot Grrrls reading or hearing about second wave feminists would have had exactly that benefit. Kathleen Hanna had extremely similar memories of Riot Grrrl meetings, especially those that dealt with issues of rape. Marcus tells us that “hearing these girls talk openly with one another about their past traumas, watching how supportive the girls were of one another, Kathleen felt she was witnessing one of the most beautiful things in the world.”10 Moreover, the same importance of a safe community is expressed within the pages of Riot Grrrl #5 itself: “it’s cool/fun to have a place we’re [sic] we can express ourselves that wont [sic] be censored and we’re [sic] we can feel safe to bring up issues that are important to us,” the author writes. Over the page, there is a harrowing story of abuse, demonstrating that the place to which the author refers does not have to be a room full of likeminded women, it could be the pages of a zine.

1. Shulman, Alix Kates, Private Interview, Zoe Guttenplan, 30/11/16.

2. http://www.redstockings.org/

3. ARCHIVES FOR ACTION PACKET: Some Documents From and Media Responses to Redstockings, http://www.redstockings.org/

4. Peslikis, Irene quoted in Ninia Baehr, Abortion Without Apology: A Radical History for the 1990s, Boston, MA: South End Press, 1990, 42.

5. Personal Interview.

6. Baumgardner, Jennifer, F 'em!: Goo Goo, Gaga, and Some Thoughts on Balls, Berkeley, CA: Seal Press, 2011, 49.

7. Personal Interview.

8. Ibid.

9. Forer, Anne quoted in Susan Brownmiller In Our Time, New York: The Dial House, 1999, 21.

10. Marcus, Sara, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, New York: Harper Perennial, 2010, 38.