“There was no internet, there was mimeograph and stamps.” Mary Jean Collins in She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry.

The proliferation of office Xerox machines in the 1960s made producing one’s own zine “inexpensive and accessible to most in the industrial world.”1 The economic aspect was crucial to zine-making punks who rejected the dominant consumer culture and as result did not focus on monetary profit. In his Zinester’s Guide, media and culture scholar Stephen Duncombe argues that the zines were “less a means to an end than the ends in themselves.”2 The fact that the technology needed to create a zine existed in most offices allowed almost anyone to share their opinions and personal stories through this medium. Indeed, the early editions of Riot Grrrl were Xeroxed by “whichever of the girls had a good copy scam running at a local copy shop or a parent’s office.”3

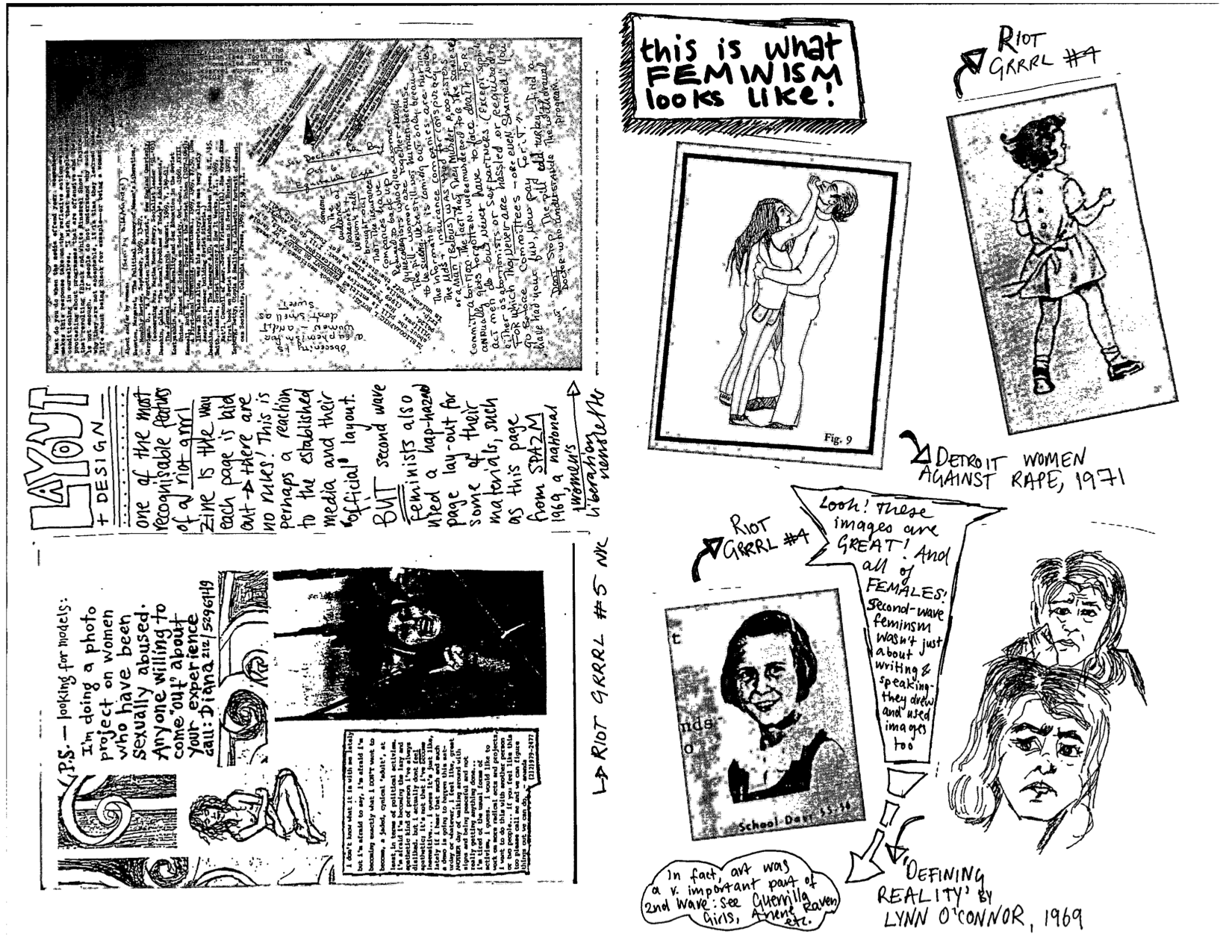

Through the format of the zine and its method of distribution the riot grrrls achieved a political radicalism aside from the content. The DIY that is evident from the cut-and-paste graphics, to the typewritten rants and hand-drawn illustrations, to the word of mouth and friend-of-a-friend circulation breaks down the barrier between producer and consumer. Dunn identifies this division as “the foundation of consumer culture,” and it is precisely this mainstream societal value system that Riot Grrrl sought to challenge.4 If the Xerox was the machine of the riot grrrl movement, the mimeograph was its older sister. Also called a “stencil duplicator,” the mimeograph used a stencil, often created by punching holes through a coated fibre sheet with typewriter keys, through which ink can pass.5 Much like the Xerox, it was cheap, accessible technology and meant that every woman at meeting could receive a copy of the latest article – ‘The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm’ for example – and distribute it among friends.

According to Susan Brownmiller, probably the “first Women’s Liberation Group in the nation” was born, in part, from a mimeograph machine. At the 1967 National Convention for New Politics, where liberals had gathered to examine a third-party campaign for the ’68 election, a women’s workshop met to discuss getting women properly organized in anti-war activism. Just as Riot Grrrl exists partly due to the energy of its founding members, Women’s Liberation kicked off because of the firecracker personalities of Jo Freeman and Shulamith Firestone. These women worked through the night in the mimeo room putting together a resolution demanding that women delegates receive 51% of the convention votes, and condemning the sexism rife in society. When Firestone charged the podium, the session chairman told her to “calm down, little girl.” This Chicago group first met a few days later, and “talked incessantly.” Over the next two years they would put out seven mimeographed issues of a national newspaper, Voice of the Women’s Liberation, which had eight hundred subscribers across the nation when it closed.6

Mimeographed materials also have a similar tactile quality to zines. They’re flimsy and easy to make in a way that defies the slick professionalism of mainstream media. “I had trouble with the mimeograph stuff,” Brownmiller admits. “It’s amazing, but it had its own form of writing – humble, the writing not the ideas, the ideas were revolutionary. I was freelancing for popular newspapers at that time, training myself to be an objective reporter. There was no way I could do the mimeograph stuff.”7 Brownmiller took time off from activism to finish her groundbreaking book on rape, Against Our Will, only returning for a few actions and speak-outs. She still speaks overwhelmingly positively about the Women’s Liberation Movement, recalling “how absolutely extraordinary it was” to hear women talking about abortion out loud for the first time and that “the excitement of having something to say about women's lives, and finding avenues to express them, was so great that our ideas bounced around the country and as far as Australia.”8 The enormous geographical scope of the second wave writings is in part due to the technology used to print them. Not only did the mimeograph make it cheap to distribute materials, but there is an urgency in the messy, smudged quality of the printing that conveys immediacy and need for action which is also seen in Riot Grrrl zines.

1. Dunn, Kevin, Global Punk: Resistance and Rebellion in Everyday Life, New York: Bloomsbury, 2016, 164.

2. Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, Bloomington, IN: Microcosm Publishing, 2008, 76.

3. Marcus, Sara, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, New York: Harper Perennial, 2010, 110.

4. Dunn, 171.

5. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Mimeograph." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. September 12, 2008. Accessed December 01, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/technology/mimeograph

6. All information and quotations in this paragraph are from Brownmiller, Susan, In Our Time, New York: The Dial Press, 1999, 17-18.

7. Brownmiller, Susan, Personal Interview, Zoe Guttenplan, 05/12/16.

8. Ibid.