Early history of American punk rock is full of women such as Patti Smith in the east and the Go-Go’s in the west. But as the ‘80s drew on, hyper-masculine bands emerged, especially along America’s West Coast.1 These had a more aggressive sound and performed a consciously macho persona, so it’s no wonder that the mosh pit became a place for violence and anger. Jennifer Miro of the punk band Nuns remembers that “women didn’t go to see punk bands anymore because they were afraid of getting killed.”2 At the turn of the decade, Tobi Vail and Kathleen Hanna had just started their female punk-rock band Bikini Kill. With their diverse experiences and versions of feminism, they came up with the title Revolution Girl Style Now to describe their shared vision. Tobi already produced a fanzine, Jigsaw, which Sara Marcus describes as “thick and hyperliterate” and gave a copy to University of Oregon freshmen Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman.3 A year later, they had come out with Girl Germs, a zine that Molly printed on the copy machine of a Capitol Hill office where she has interned in high school.

In Spring 1991 Bratmobile, the band that Molly and Allison had started with almost no experience, went to DC and recruited Erin Smith, the girl behind Teenage Gang Debs, a fanzine about old TV shows. During that same week, they met DC scenester Jen Smith. Jen was in DC through the Cinco de Mayo riots of 1991 that erupted after a Salvadoran immigrant was shot by a police officer. It was a combination of these riots and the Supreme Court’s upholding of the gag rule that wormed their way into her mind and prompted her to write a letter to Allison about the upcoming summer containing the words “girl riot.”4 When Revolution Summer Girl Style Now finally came, the DC city murder rate hit an all-time high, and protest felt relevant. The bands were on hiatus due to the absence of some members, and so looking for other ways to fill their time. To a certain extent, Riot Grrrl was born out of a typical school’s-out-boredom familiar to many college students. However, it was more than just something to do. Kathleen, Molly, Allison, and Jen Smith wanted a way to maintain and create connections with other girls in the DC scene; the sisterhood aspect of the Riot Grrrl movement was there from the very beginning.5

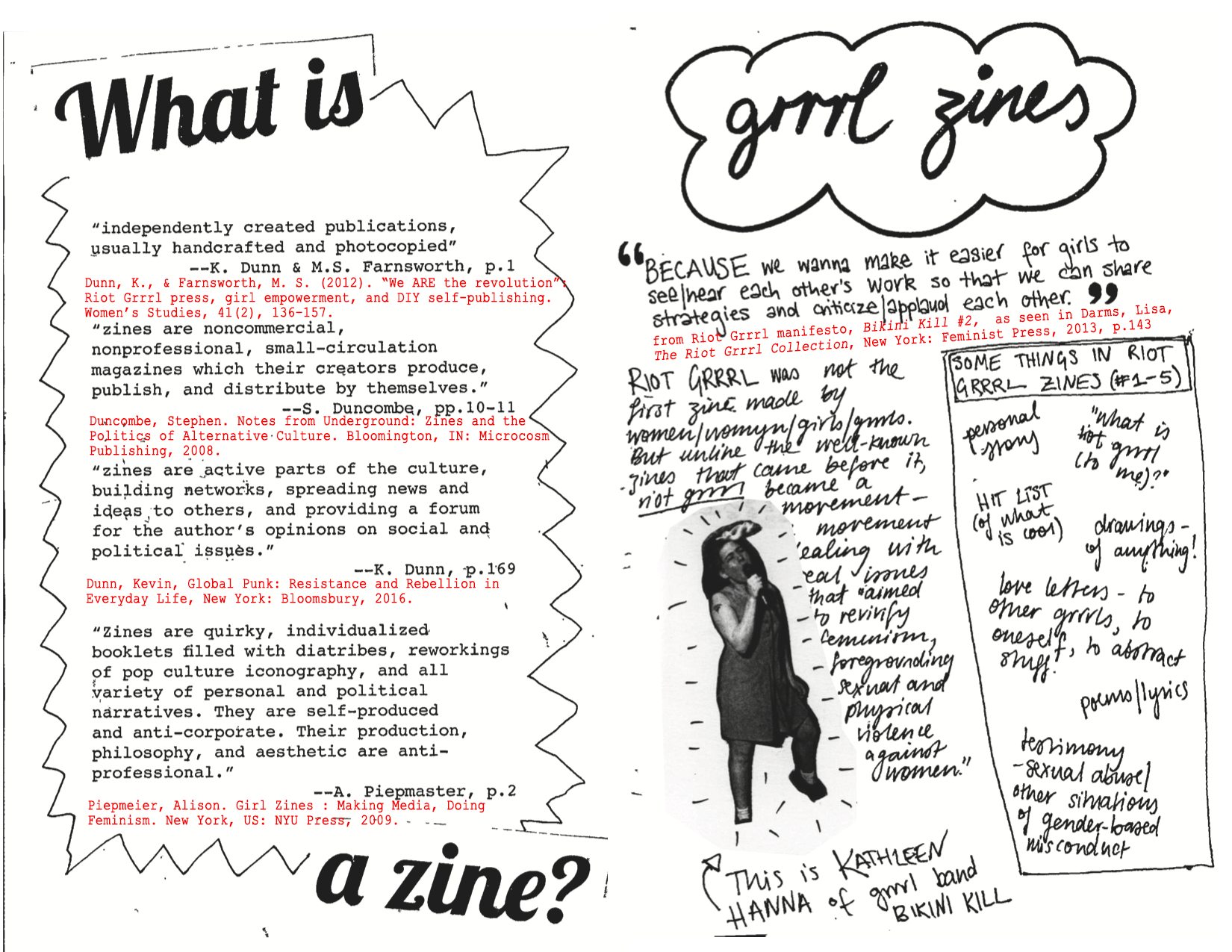

The DIY style of punk-rock exhibited by Bratmobile’s courageous venture into a virtually unknown realm is also crucial to the zine world. The first issue of Riot Grrrl was printed on Molly’s dad’s office copy machine and the front cover declares: “riot grrrl is a free weekly mini-zine. Please read and distribute to your pals.”6 The girls distributed it at a July 4th BBQ held in Erin’s parents’ back-yard at which Bratmobile played their first show of the summer. Issue 2 was handed out at a free show in Fort Reno Park. Not only were the bands and the zines DIY, but the movement completely embodied the self-creating sensibility. The title of the zine itself formed the community that took its name, and simultaneously they formed it. Marcus acknowledges this power of a name, and posits that Riot Grrrl “created its audience of girls by naming them, radicalized them by addressing them as already radical.”7 However, there was also an emphasis on self-definition. As Kathleen Hanna wrote in the second issue of her zine Bikini Kill: “I encourage girls everywhere to set forth their own revolutionary agendas from their own place in the world.”8

The narrative of how Riot Grrrl came into existence that Kevin Dunn, Stephen Duncombe, and to a certain extent Sara Marcus tell all position music as the central issue around which the women rallied. This gives music an importance which perhaps it is not quite due. However, even if riot grrrls did start with music and move on from there, they were not alone in the history of feminism. “There were no female musicians in the orchestra, except the harpist,” Alix Shulman said, speaking of the 1960s. “And of course there were singers, because of their unique vocal range.” One of the early things that second wave feminists fought for was blind auditions. After that, the orchestra was approximately half male and half female. Naomi Weisstein’s Women’s Liberation Rock Band, which started in Chicago and moved to New Haven “was the beginning.”9 Weisstein herself acknowledges the connection between her project and Riot Grrrl in a 2014 article in New Politics. She writes:

“All our lives, we girls had been taught that male abuse was sexy…how could a feminist combat this? [...]Riot Grrrls-inspired feminist rock bands were at least twenty-five years away. (For example, Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney-not to mention Pussy Riot, which was still forty-five years away.)”10

Although the music of Riot Grrrl was punk, and Weisstein’s more traditional Rock and Roll, both musical projects were at the edge of popular music, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable not just for women but for anyone. However, for women in particular, these were spheres where they were not normally seen. Both musical scenes were perceived as grimy and aggressive – certainly not a place where respectable young women would go.

Moreover, the punk rock scene was the epicenter of subversive culture in the ‘90s. The “Armageddon” of the first half of 1968 made the culture of the late 60s/early 70s a political culture.11 Riot Grrrls had something else to join their politics to, but the Second Wave feminists just had to create the politics from their own lived experience. Punk and zines were the tools given to Riot Grrrls by 90s pop culture, but in the 60s, pop culture had been superseded by revolution so the tools of the second wave feminists were “protests and pamphlets.”12 New York Radical Women were, in some ways, a reaction the New Left in the same way that Riot Grrrl was a reaction to macho punk rock. That is to say, neither movement was entirely a product of the male-dominated spheres that they grew out of. The legacy of women coming together was important to both, and both took that which those before them had started and made it their own. For riot grrrls, who joined “Second Wave theories with punk rock and DIY culture,” this looked like a “tuff” girl attitude and a gritty aesthetic.13

1. Marcus, Sara, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, New York: Harper Perennial, 2010, 49.

2. Miro, Jennifer quoted in Sofia Klatzker “Riot Grrrl” quoted in Kevin Dunn, Global Punk: Resistance and Rebellion in Everyday Life, New York: Bloomsbury, 2016, 41.

3. Marcus, 42.

4. The gag rule refers to Rust v. Sullivan, in which the Supreme Court upheld that “Should government subsidize one protected right (family planning), as it does in this case, it does not follow that government must subsidize analogous counterpart rights (abortion services)” ("Rust v. Sullivan." Oyez. Chicago-Kent College of Law at Illinois Tech, n.d. Oct 9, 2016. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1990/89-1391)

5. For my timeline of the inception of Riot Grrrl, I used Sara Marcus’ Girls to the Front as my main source of information, but this was corroborated by the short documentaries Don’t Need You: Herstory of a Riot Grrrl and The Punk Singer.

6. Darms, Lisa, The Riot Grrrl Collection, New York: Feminist Press, 2013.

7. Marcus, 81.

8. Darms, 128.

9. Shulman, Alix Kates, Private Interview, Zoe Guttenplan, 30/11/16.

10. Weisstein, Naomi, “The Chicago Women's Liberation Rock Band, 1970-1973,”New Politics,15(1), 2014 34-42.

11. Brownmiller, Susan, In Our Time, New York: The Dial House, 1999, 24.

12. Baumgardner, Jennifer, F 'em!: Goo Goo, Gaga, and Some Thoughts on Balls, Berkeley, CA: Seal Press, 2011, 50.

13. Ibid, 49; “The Armed Citizen,” Riot Grrrl #4, ~1992.